The bunks inside the dongas all looked like this, but this is the special one for the OiC. He had his own desk.

Why, they pull out their weighty and learned science text books, brush up on their quantum physics and double check all their instruments are working before retiring early to do the same again on Sunday. Yeah, right!

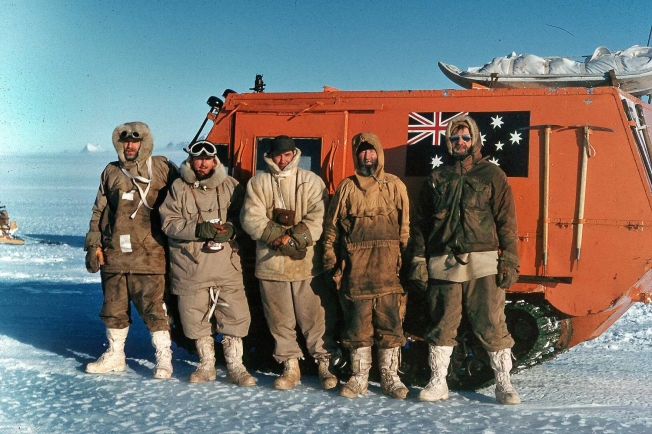

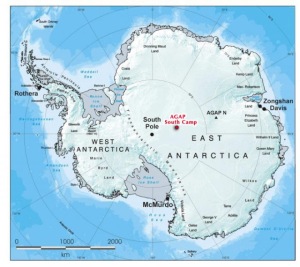

Let me set the scene in this little base in Antarctica for our first Saturday night in early March 1957.

There are twenty scientists and mechanics and the cook. The Kista docked on Friday 17 February 1956 and left 12 days later. (1956 was a leap year).

While the departing team was packing and getting on the ship, the wintering team was unpacking the cargo holds and getting off the ship and there were several days of blizzard when none of the above was happening.

At the time Mawson station was composed of Biscoe Hut. The A-frame Norwegian hut arrived with the pioneers in 1954 and served as mess hut, kitchen and accommodation. The first team in 1954 also brought four dongas that served as laboratories, and the power station where the diesel generator was housed. It supplied electricity to all five huts until it burnt down in 1959.

Bisco had eight square metres of space. The 1954 pioneers put five bunks down each side, an AGA stove and sink at the western end, a table in the centre and there was a porch on the eastern end which contained the toilet and meteorological equipment. That was pretty cramped but there were only 10 of them.

I’m not sure if the1955-6 winterers brought any buildings with them (perhaps someone can write in and tell me).

Our 1956-7 winterers were positively bristling with buildings. The 1957 winterers are a team of 20, so their priority was to find the packing cases which contained the four pre-fabricated laboratory and accommodation huts. Three days after they arrived, on 20 February 1956, Syd Kirkby reported that the huts were “going up like steam. The blokes put up the outside shells of two today and another two days should finish them, afraid the hangar will be a different story.”

Inside each of these tiny, the prosaic, bolted together, plywood dongas, six men slept in two rows of triple decker bunks. The doctor slept in the surgery, which was also a donga. No doubt you’ve already done the maths. They hadn’t been planning on having twenty in the party, so someone had to sleep in the cold porch of one of the huts. There are only so many places where pee bottles can be stored so it wasn’t a great honour to be the man on the porch.

The new buildings allowed Biscoe Hut to become just the mess hall. It was lit through four skylights or at night by a thin stream of electric lights. Biscoe is lovely again thanks to the restoration work of the heritage carpenter Mike Staples who began restoration work on it from ruin in 2006. I was extremely lucky to be chosen as an Arts Fellow in the 2007/08 season and it already looked wonderful then.

The 1957 winterers also brought with ANARE’s first and the pre-cut metal plane hangar. For years the plane hangar was the biggest building in Antarctica and it was all put together by the 1957 winterers, none of whom had been employed as builders. They worked with with spanners in roaring winds, without any heavy machinery.

They started the hangar while the Kista was still in harbour, while two other teams worked on the dongas. On the Sunday, 26 February 1956, under an overcast sky driven, in intermittent forty-knot winds, the metal plane hangar began to take ghostly form: with “one bay up and the mast moved to the second position.” The planes were stored on the ship for as long as possible to protect them against the weather. The hangar was finished in March.

So back to my opening question. What do you think this team of overworked winterers did to celebrate their first Saturday in Antarctica?

On that, as with every Saturday night, there was a formal dinner (complete with shirt, tie, and jacket), followed by movies that were accompanied by lashings of home brew. That year the camp had ten feature-length films to last the year, supplemented by wartime propaganda films on how to build spitfires, how to defeat the beastly Germans, and how to gain the advantage in hand-to-hand combat. From the BBC came a collection of greatly-loved, shellac audio disks of Churchill’s wartime speeches.

On that first Saturday night, on Sat 10th March 1956, it was Jim McCarthy’s birthday. After the dinner, they pushed back the tables and played insanely boisterous indoor football. That night it was “Rugby versus Australian Rules. In the morning the doctor cheerfully dealt with: a cut cheek, a split lip, a cut requiring two stitches over one eye, a swollen nose, one black eye, and a ‘marked face.”

“I guess we will make this a regular ding feature, I reckon it is the best way in the world to help a mob living happily together, we work off steam that otherwise may come out as blues and being as we are, the more we knock each other about the better mates we become,” was the young surveyor’s philosophical summary of the event.

![Pageflex Persona [document: PRS0000443_00063]](https://quillswritingtuition.files.wordpress.com/2014/05/book-cover-3-reworked-in-may-copy.jpg?w=652&h=398)