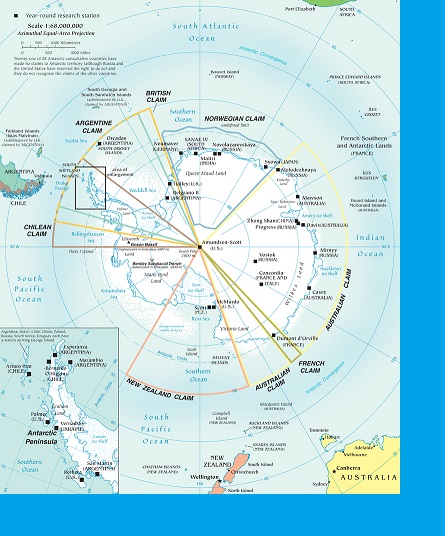

In early November, Phil’s approval for the Southern Journey finally came through, and the process of dropping fuel depots increased the pilots’ workload. RAAF squadron leader Douglas Leckie faced one of the greatest challenges of his career. Having flown Bill and Peter out to a staging depot at the north of the Prince Charles Mountains, he landed before realizing that he’d put the plane down in drifting snow which hovered over a crevassed area amidst blue ice. Unwilling to take off with passengers, he dumped out the survival tent and food before taking off, planning to return with better visibility to find a safer landing. He refuelled at Mawson and flew back to the depot by himself, but there was no trace of Bill and Peter—or even a sign that they had ever been there. He searched until he needed to refuel, went back to Mawson, refuelled and returned, scouring the white ground with tired eyes. Peter and Bill had just the barest of survival gear in snow-covered crevassing.

Doug Leckie at the Beaver controls

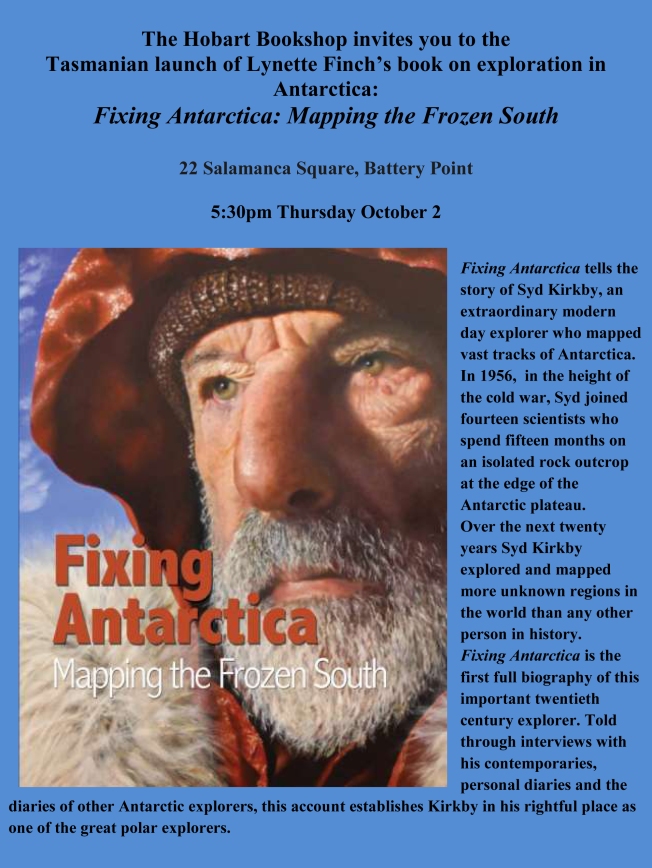

Syd arrived back at Mawson at the same time as Doug landed the Beaver for the third time, ashen grey, deeply distressed, and very fatigued. Syd and Jerry Sundberg joined the hunt as Doug fretted that he was no longer sure where he had left Peter and Bill. Syd spotted them through a gap in the twenty-feet-deep drifting snow, where they’d been all along, able to hear the aeroplane above them the whole time Doug circled. Now the problem was that there were five men to get home. Against Syd’s suggestion that he would get out with more gear and stay the night with the other two, Doug simply refused to leave anyone there.

The overworked plane took off into the mountains, with its nose pointing down in the full-flap altitude. At that site they established 250-mile depot, or Southern Depot, over the next few weeks, knowing that, as much as they would have liked the aircraft to be available for support while they were sledging, the Mawson landing strip was on a sea-ice surface that was about to disappear.

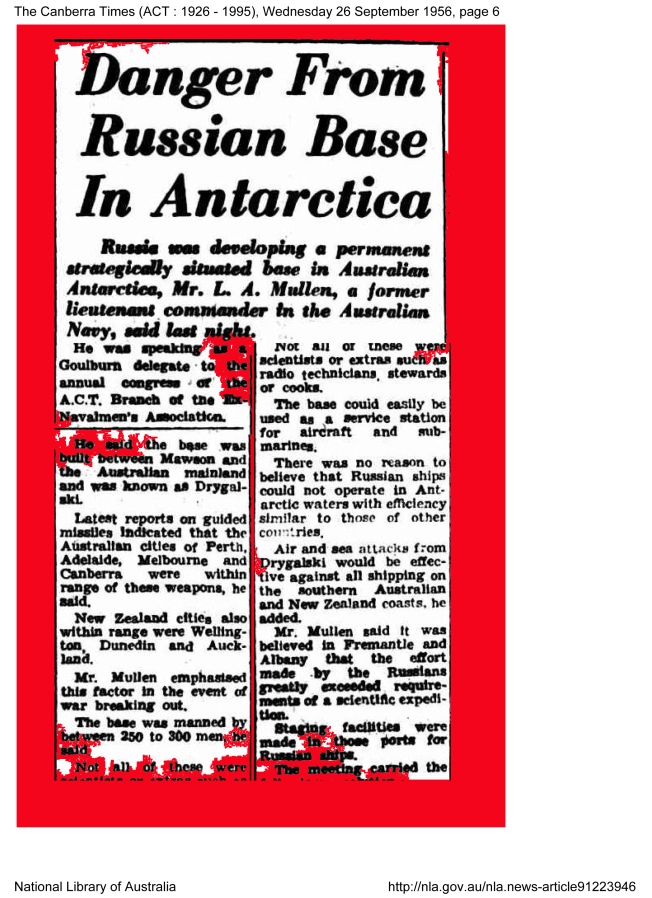

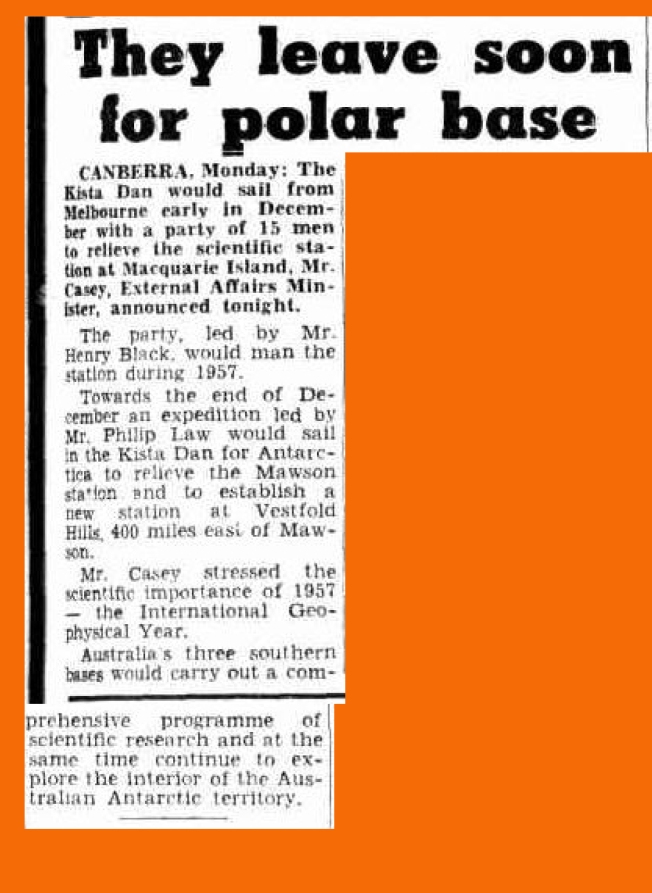

At the Southern Depot, Doug and John constantly dumped supplies, seal meat, human food, fuel, and spare parts for the weasels. The field party switched to thirty-hour cycles. A five-man party was assembled. Bill Bewsher, as party leader, Peter as geologist, Lionel Gardner, the senior diesel mechanic, John Hollingshead, the radio technician, and Syd as navigator and surveyor would travel with two weasels and lightly laden dogs. On Sunday, 18 November 1956, the Mawson expeditioners held “a fine ding,” all wanting the ten-week one-thousand-mile polar plateau journey to be a success. Syd sent home a YIKLA (this is the life), but the note in the diary he left behind at Mawson farewelled his family:

On this night, the beginning of what will probably be one of the most important periods in my life, I make thanks to my family for all they have given me. Not only the educational advantages but the whole patterns of our life. To Joy I say ‘God Bless you Darling, I have been very happy and helped greatly by the thought of you’.

Five men, eight dogs, and two weasels left Mawson at 1030 on Monday, 19 November 1956, with “a deafening click of camera shutters and hands wrung to a pulp by well wishers.” The sledging party packed three novels: Oblomov, The Three Musketeers, and The Odyssey. Australia’s most ambitious inland Antarctic exploration was underway, and the weather was lovely.

if I am worthy to carry the frayed banner they have passed to us. Theirs is the past, ours is the future, how will we show in a hundred—or even fifty or twenty years—one thing is sure those giants of old shall never be eclipsed.